The question of who is responsible for the rise of communalism in India is complex and multifaceted. While the British colonial administration undeniably played a significant role in institutionalizing divisions between religious communities, it would be an oversimplification to place sole blame on them. The seeds of communalism have historical, social, political, and economic roots that predate British rule and extend into post-independence India.

This article explores the role of the British in fostering communalism while examining other contributing factors to understand the broader context of communal tensions in the Indian subcontinent.

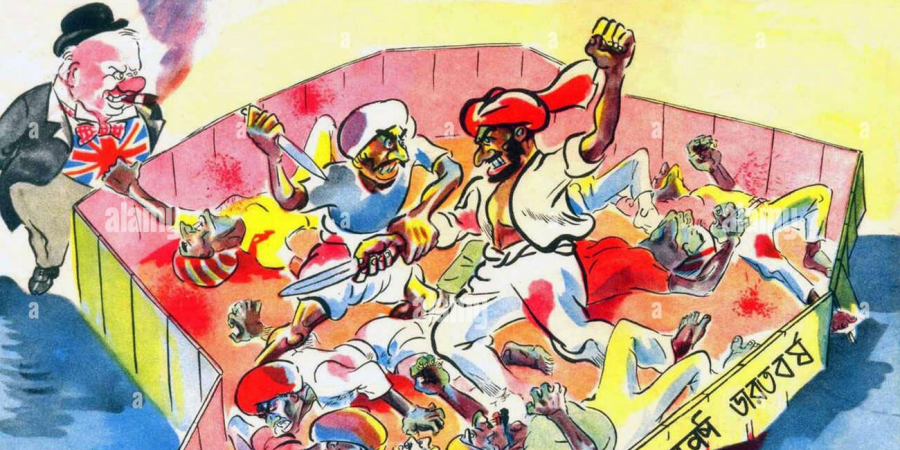

The Role of the British: Divide-and-Rule

The British colonial administration is often accused of deliberately fostering divisions between Hindus and Muslims to consolidate their rule. Several policies and practices substantiate this claim:

Institutionalizing Religious Identities:

- The British introduced religious classifications in censuses, elections, and administrative policies. These measures hardened religious identities, which were earlier more fluid and localized.

- By creating separate electorates for Hindus and Muslims under the Indian Councils Act of 1909 (Morley-Minto Reforms), the British formalized communal politics.

Partition of Bengal (1905):

- The division of Bengal into Hindu-majority and Muslim-majority areas was seen as a deliberate attempt to weaken nationalist sentiments by dividing communities along religious lines.

Communal Representation:

- The British encouraged communal representation in legislative councils, amplifying religious identities at the expense of national unity. The Government of India Act of 1935 further institutionalized communal electorates, deepening divisions.

Exacerbation of Communal Tensions:

- The British often supported one community against the other to suppress uprisings or maintain control. For instance, during the 1857 Revolt, the British portrayed it as a "Muslim conspiracy" to alienate Hindus, and later as a "Hindu uprising" to pacify Muslims.

Fostering Communal Organizations:

- The British supported the formation of organizations like the Muslim League to counter the Indian National Congress, which advocated for a united India. The divide between the two organizations eventually contributed to the demand for Pakistan.

Historical Factors Predating British Rule

Communalism in India did not originate solely during the British era. Pre-existing socio-political dynamics also played a role:

Medieval Rulers and Religious Policies:

- While rulers like Akbar promoted religious tolerance, others, such as Aurangzeb, implemented policies that were perceived as favoring one community over another. Such instances contributed to mutual distrust over time.

Economic and Social Divides:

- Hindu and Muslim communities often occupied different social and economic roles. For instance, Muslims were historically associated with ruling elites, while Hindus dominated trade and agriculture. These distinctions sometimes created resentment.

Local Conflicts:

- Instances of local disputes over land, temples, mosques, or cattle were common in pre-British India. These conflicts, while often economic or social in nature, sometimes took on a communal dimension.

The Role of Indian Elites and Political Organizations

While the British laid the groundwork for communalism, Indian leaders and organizations also contributed, sometimes unintentionally:

Hindu and Muslim Revivalism:

- The 19th century saw the rise of organizations like the Arya Samaj and Aligarh Movement. While their primary goal was internal reform, their rhetoric sometimes created divisions by emphasizing the distinctiveness of their communities.

The Indian National Congress and the Muslim League:

- While the Congress initially sought to represent all Indians, its inability to fully address Muslim concerns led to the rise of the Muslim League. Both parties, at times, engaged in communal politics to secure their constituencies.

Communal Riots:

- Leaders from both communities sometimes used communal sentiments to mobilize support. Communal riots, such as those in the 1920s and 1930s, further deepened mistrust between Hindus and Muslims.

Post-Independence Communalism

Even after independence, communalism persisted, suggesting that the issue is not solely attributable to the British:

Partition and its Aftermath:

- The partition of India in 1947 was accompanied by horrific communal violence, leaving deep scars on both communities. The legacy of partition continues to influence communal relations.

Political Manipulation of Religion:

- Indian political parties have frequently used religion to mobilize support. The rise of Hindutva politics, as well as accusations of "minority appeasement," has further polarized communities.

Socio-Economic Disparities:

- Economic and educational disparities between Hindus and Muslims have contributed to communal tensions. Reports like the Sachar Committee (2006) highlight the marginalization of Muslims, creating grievances that can be exploited politically.

The Role of Civil Society and Media

Media Amplification:

- The media has sometimes sensationalized communal issues, worsening tensions between communities.

Civil Society Efforts:

- On the positive side, grassroots organizations and movements have worked to foster interfaith dialogue and reduce communal mistrust.

Conclusion

While the British played a significant role in institutionalizing communalism in India through their divide-and-rule policies, they cannot be held solely responsible. Communalism has roots in pre-colonial socio-economic dynamics, was exacerbated by Indian political movements, and persists in contemporary politics and society.

Understanding and addressing communalism requires a nuanced approach that goes beyond assigning blame. India must focus on promoting inclusive policies, fostering interfaith understanding, and addressing socio-economic inequalities to overcome the legacy of communal divisions and build a united future.