Latin America has a complex and layered history when it comes to narcotics. This region has long been associated with drug cultivation, distribution, and the struggles related to drug trade violence, corruption, and international intervention. Yet, the history of narcotics in Latin America is deeply interwoven with indigenous practices, colonial exploitation, political upheavals, and socioeconomic factors that have collectively shaped the drug landscape we see today. This article delves into the historical trajectory of narcotics in Latin America, examining its origins, evolution, and the forces that have propelled Latin America to the center of the global drug trade.

The use of mind-altering plants has a long history in Latin America, dating back thousands of years. Indigenous cultures across the region used plants like coca, peyote, and mushrooms for medicinal, spiritual, and ceremonial purposes. These plants held significant cultural and religious value and were often revered as sacred. For example:

Coca Leaf: In the Andean regions, the coca leaf was chewed by indigenous communities for its stimulant properties. It helped people cope with the harsh mountainous environment by reducing fatigue, hunger, and altitude sickness. The Incas considered coca a gift from the gods, reserved primarily for the elite, though its use spread widely over time.

Peyote and Psilocybin Mushrooms: Various indigenous groups in Mexico and other parts of Latin America used peyote (a cactus containing mescaline) and psilocybin mushrooms as part of spiritual rituals. These plants were thought to bring the user closer to the divine, with shamans using them to enter trances and communicate with the spiritual world.

In these pre-colonial times, narcotic plants were not considered illicit or harmful but rather integral to the cultural and spiritual life of many communities.

With the arrival of European colonizers, the indigenous use of narcotics took on new dimensions. Colonizers quickly recognized the potential economic value of these plants and sought ways to capitalize on them. However, Europeans were often ambivalent about indigenous narcotic practices, alternately banning or exploiting them.

Coca in the Global Market: Cocaine, derived from the coca leaf, was first isolated by European scientists in the 19th century, leading to its widespread use in Europe and the United States. Cocaine quickly became popular in Western medicine and was even included in early formulations of Coca-Cola. Demand for coca increased, and cultivation expanded in Peru and Bolivia. However, as the addictive properties and negative health impacts of cocaine became evident, countries began banning or restricting its use by the early 20th century.

Opium in Mexico: Opium cultivation in Mexico, largely introduced by Chinese immigrants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, marked the beginning of opium production in the region. Opium poppies were initially grown for local use, but demand surged with the onset of World War II when the United States required morphine for its troops. Opium cultivation continued in Mexico even after the war, setting the stage for the country’s later involvement in the global heroin trade.

After World War II, the global narcotics trade began to take on a more organized and commercialized structure, with Latin America at its center. The United States, as a primary consumer of drugs, played a significant role in shaping the Latin American narcotics landscape.

Colombia and the Marijuana Boom: In the 1960s and 1970s, Colombia became a primary exporter of marijuana to the United States. The profitability of the marijuana trade attracted Colombian criminal organizations, who began to expand operations and seek more lucrative ventures.

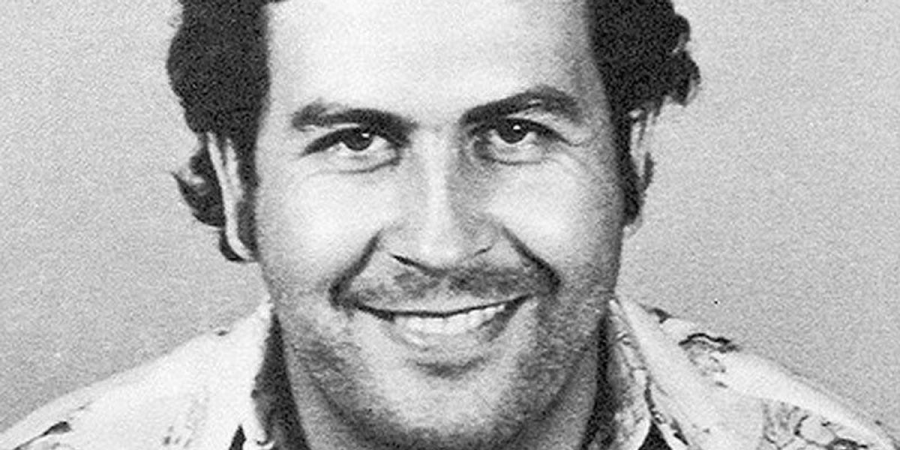

The Emergence of Cocaine Cartels: The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of powerful cocaine cartels in Colombia, most notably the Medellín and Cali cartels. Colombian cartels controlled the global cocaine trade, producing and transporting vast quantities of cocaine to the United States and Europe. Drug kingpins like Pablo Escobar became notorious, amassing immense wealth and power while unleashing unprecedented levels of violence and corruption in Colombia.

Mexico’s Role as a Trafficking Hub: By the 1980s, Mexican drug traffickers had established themselves as crucial intermediaries in the cocaine trade, transporting Colombian cocaine across the U.S.-Mexico border. Mexican drug trafficking organizations, such as the Guadalajara Cartel, emerged, eventually evolving into the dominant drug cartels we see today.

In the 1980s, the United States launched the “War on Drugs,” a major policy shift that sought to combat the supply and demand for narcotics through aggressive enforcement and militarized intervention, both domestically and in Latin America.

U.S. Intervention and Militarization: The U.S. provided billions of dollars in military aid to Latin American countries, aiming to eradicate drug production at the source. Programs like Plan Colombia funded anti-narcotics operations, including crop eradication and military campaigns against drug cartels. However, these efforts often displaced rural communities, increased violence, and did little to curb drug production in the long run.

Mexican Drug Wars: As Colombian cartels weakened, Mexican cartels became increasingly powerful, leading to violent competition among them. In 2006, Mexico’s government launched a military offensive against the cartels, sparking a wave of violence that has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives. The power vacuum created by the targeting of cartel leaders has led to the fragmentation of cartels and even more intense violence.

Social and Economic Consequences: The drug trade has had devastating impacts on Latin American society. Beyond the violence, the drug trade has fueled corruption, undermined governance, and perpetuated cycles of poverty in drug-producing regions. Rural communities often rely on drug cultivation as an economic lifeline, as drug crops can be far more profitable than traditional agriculture.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the failure of punitive approaches to effectively curb narcotics production and trafficking in Latin America. As a result, some Latin American countries have started to explore alternatives:

Decriminalization: Countries like Uruguay have experimented with decriminalizing or regulating certain drugs. Uruguay, for example, became the first country in the world to fully legalize the production, sale, and use of marijuana in 2013. This move was intended to reduce the black market’s power and provide a safer alternative for consumers.

Crop Substitution Programs: Programs to encourage farmers to replace coca and opium poppies with legal crops have had mixed success. Although well-intentioned, many of these programs struggle due to inadequate funding, infrastructure, and market access for alternative crops.

Rethinking International Drug Policy: Several Latin American leaders have called for an end to the War on Drugs, arguing that a public health approach would be more effective than criminalization. This perspective has gained traction as countries witness the limited impact of enforcement-based strategies and the toll of drug-related violence on society.

The history of narcotics in Latin America reflects a complex interplay of cultural practices, economic imperatives, international demand, and political responses. While Latin America’s role in the drug trade is often viewed through the lens of crime and violence, it is essential to understand the historical, social, and economic factors that have contributed to this reality.

Today, Latin America stands at a crossroads. While the traditional approach to narcotics control has had severe repercussions, emerging models of decriminalization, regulation, and public health-oriented policies offer hope for a future where the cycle of violence and exploitation can be broken. The history of narcotics in Latin America is still being written, and the choices made in the coming years will play a crucial role in shaping the region’s future.